A Formula for Finding the Right Elementary School

October 2, 2017 Leave a comment

My son is going to start kindergarten next year. That means that my wife and I are presented with an issue that is commonly faced by young families in the city at about this time: should I stay or should I go?

Philadelphia, by and large, does not have great schools. The district‘s overall rating on Great Schools is a three out of ten. There are a few decent elementary schools, but they are all located in very expensive neighborhoods, and some are so crowded that they’ve started having a lottery for kindergarten classes, so there’s no guarantee that your kid will get to go to that school just because you live in its catchment area.

On the other hand, Philadelphia’s suburbs are home to some of the best schools in the country. On Niche’s 2018 Best School Districts in America list, three of the top 25 are in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. Unfortunately, most of these areas lack a lot of the amenities that we’ve become accustomed to in Philadelphia: their walk scores are lower, and the commute times back to Center City would be higher.

So, how do we objectively weigh the desire for great schools with the desire for a walkable environment? With math! All I needed was a formula to determine what areas were worth looking at in greater detail. Through a process of trial and error, and through lots of discussions with my wife, I determined what factors are important to us in a location, and weighted those factors based on which ones mattered most. So here are our variables:

Great Schools Score

Great Schools rates nearly every public and charter school in the country on a ten-point scale. The rating is based primarily on state-level standardized tests, so comparing schools across state lines isn’t exactly apples-to-apples, but the fact that it covers so many schools still makes it one of the best measures for determining school quality. In some areas, student progress and college readiness are also taken into consideration when assigning a school a rating.

Presence of a Playground

As I began looking at schools in my neighborhood, I was surprised to find that most of them don’t have playgrounds. I wonder if this is an aspect of our suburban upbringing, but my wife and I had just assumed that all elementary schools had playgrounds: between the two of us we attended five elementary schools, and each of them had its own playground (several of the ones I attended had one for smaller kids and a second one for bigger kids). In addition, all the schools that I looked at outside of Philadelphia have their own playgrounds. For my wife and I, although we haven’t thought of a lack of a playground as a deal-breaker, we have heavily weighted schools that have a playground over those that don’t.

Walk Score

Walk score is a measure of the walkability of a neighborhood, or how easy it is to get to goods and services on foot, without getting in a car. Areas that have a walk score over 70 are considered “very walkable.” Most neighborhoods in Philadelphia have a walk score over 90, which makes them “walker’s paradises.” Of all the neighborhoods my wife and I have lived in, the one that had the lowest walk score that we considered acceptable was about 80, so I’m cutting off areas with a walk score below 80 from this analysis.

Median Home Value

I gathered the median home value at the census tract level from the 2015 American Community Survey. I’m using this as a measure of affordability, so generally, the lower the median home value, the higher the score. That being said, there are many neighborhoods in Philadelphia where housing prices are extremely low because they are less desirable neighborhoods. Therefore, I cut off the extra points for cheapness at $100,000.

Commute

I work five days a week in Center City Philadelphia. My wife work from home a few days a week, in Center City a few other days, and in Conshohocken one day a week. She also doesn’t drive. So, for us, it is very important to be able to get to Center City via transit, slightly less important to be able to get to Conshohocken via transit, and much less desirable if we have to drive to either of these places. In some cases it would be quicker to drive somewhere rather than take transit (especially to Conshohocken), but unless driving will save us more than a half hour or so, we’re probably going to opt for transit.

Church

My wife and I are Mormon, and Mormons are assigned to a congregation geographically based on their address. We currently are assigned to the South Philadelphia congregation, and we really like it. While we would be alright going to another congregation, if it were between one place outside of the congregation’s boundaries and an equally good place inside of them, we would go with the second.

With these variables in mind, I analyzed 251 addresses and 209 schools in the Philadelphia area, and came up with the following formula:

Score for a given address = (a – 1) + (if (b = “Y”, 1) * 8) + (((c – 80) / 20) * 7) + (if (d > 100,000, ((636,100 – d) / 536,100) * 6, 0)) + (if ((e – 30) > f, ((70 – f) / 65) * 3, ((70 – e) / 64) * 5)) + (if ((g – 30) > h, ((70 – h) / 54) * 2, ((70 – g) / 46) * 4)) + (if (i = “Y”,1))

Variables:

a = Great Schools rating for the school whose catchment area contains the address

b = Whether or not the school has a playground (Y/N)

c = Walk score of the address

d = Median home value for the census tract that contains the address

e = Commute time from the address to Center City office via transit

f = Commute time from the address to Center City office via car

g = Commute time from the address to Conshohocken office via transit

h = Commute time from the address to Conshohocken office via car

i = Whether or not the address is within my church congregation’s boundary

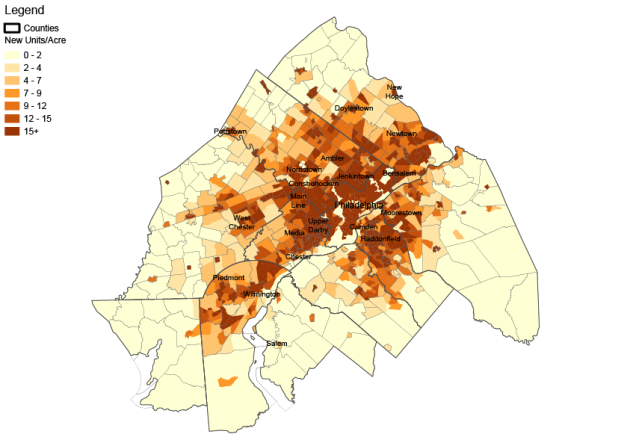

Then, these being schools, I gave them a grade, and I graded on a curve: those addresses whose scores were 90% or more of the highest score got an A, those from 80-89% got a B, etc. Here’s what that looks like on a map:

Only two schools get A’s: the Greenfield School and the McCall School. These two schools cover much of Center City. They have high Great Schools ratings (7/10); both schools have playgrounds; areas in both catchment areas have walk scores as high as 100/100; they’re within walking distance of the Philadelphia offices and have good access to regional rail stations, which means good access to Conshohocken; and parts of their catchment areas are within my church congregation’s boundaries. Really, the only downside to these areas are cost; parts of these school’s catchment areas are some of the most expensive neighborhoods in Philadelphia. For my family, in order to get into a good school in a good neighborhood, we will probably have to live on the cheaper edge of a more expensive neighborhood, and even then, we’re probably going to get less house for our dollar than we’re getting right now.

The B schools are a little different: they include the Independence Charter School in Center City, the Penn Alexander School in West Philly, and the Penn Wynne School in Ardmore. They also have high Great Schools ratings (6, 10 and 10 respectively); all have playgrounds; while lower than the A schools, their catchment areas all include places with walk scores above 90; commutes for Independence and Penn Alexander are somewhat similar to those in Center City, and the part of Penn Wynne’s catchment area in Ardmore has good regional rail access to Center City and is a fairly short drive to Conshohocken; unfortunately, only Independence would be located within my church congregation’s boundaries. Throw in that Penn Alexander has a lottery for its kindergarten class and you can see why these otherwise quality schools aren’t quite as strong of a match for us.

Beyond these schools, the good options for my family dry up pretty quick. Most other schools in the region either have low Great Schools ratings or are too far from town to make commuting the way we want to reasonable.

So, will we stay or will we go? Probably stay. Ardmore is still a possibility, but based on my analysis, a really good school in Philly is a better fit for us than a great school out in the suburbs. Now I just have to figure out how to afford Center City rent.